· 3 min read

Del Norte al Sur - How Protest Chants Transcend Language and Borders on the Picket Line

Written By Taiyea

As strikes and labor actions continue to spread across the United States, there is a pervasive narrative that organized labor has been awakened from a long slumber. But this notion of a dormant labor movement in the US is only true if we ignore the many victories won by immigrant workers of color in recent history.

Most notably, there was the 1965 grape strike led by Filipino and Mexican migrants with the National Farm Workers Association, now known as the United Farm Workers which remains active today. Even more recently in 1999, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) organized nearly 75,000, mostly immigrant, home-care workers in Los Angeles, which was the largest unionization effort in the second half of the 20th century.

These union victories certainly undermine the narrative that the labor movement has been ineffective since the 1950s. Migrant workers have been the backbone of organized labor yet their contributions still go unnoticed. Fortunately, there are signs that the times are changing.

In April of 2023, during my final weeks at Whittier College, our dining hall workers went on strike against their employer Bon Appetit (a third party company that provides food services for several institutions including USC and Dodger Stadium). The strike lasted for 27 days, which was at the time the longest indefinite strike in their union UNITE-HERE! Local 11’s history.

I was one of many students who organized in solidarity with the workers. Among our activities included fundraising, making posters, and chalking, but most important was taking part of the picket line itself. We did not have any formal training on how to lead a picket, we learned on the fly.

A significant number of the striking workers were Spanish-speakers with roots across Latin America, so Spanish-language chants were prioritized on the picket line. Student allies were more than ready to learn these chants even if they had never spoken a word of Spanish before. This included several international students from a range of countries, from Mauritius to Kazakhstan to Japan.

One of the most popular chants on the line was “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,” taken from the Quilapayún song of the same name The fact that this pro-Allende anthem from Chile in 1975 made its way to Whittier in 2023, revealed to me the power of Spanish language chants to transcend not just language and borders, but also time and space. How do chants achieve this power?

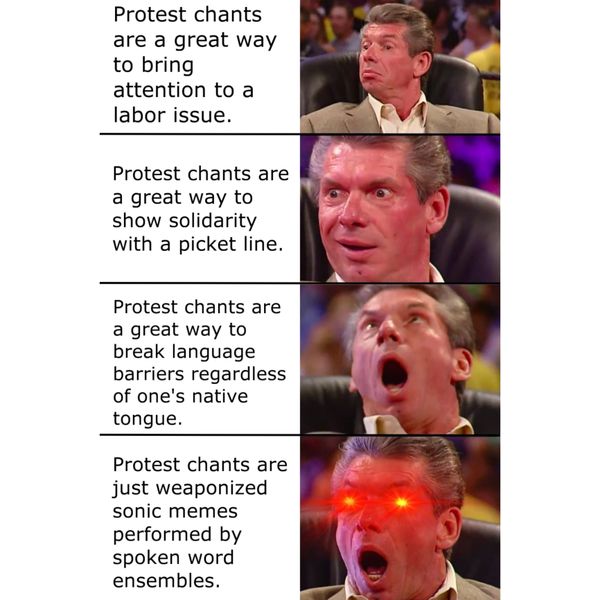

One way to answer these questions is to interpret protest chants not as language but as spoken cultural memes. Memes can be articulated as a mode of communication in which a cultural artifact provides a superstructure within which another idea can be expressed. In other words, the process of “memeing” takes a preexisting symbol and gives it new meaning.

Chants function much in the same way. While the underlying structure of a phrase may stay the same, keywords are swapped out depending on the situation. This is most apparent when the same chant is repeated in multiple locations - as over the course of this summer I heard “Whittier, escucha!” become “Los Angeles, escucha” and later “Long Beach, escucha.” But even at a single picket line this memeing occurs. When one gets tired of chanting “el pueblo unido” they can switch to “mi gente unido,” or “trabajadores unidos.”

Of course, there is something lost in translation in this process. But let us also consider what is gained. When I was volunteering at a hotel picket line in downtown LA, where the only person who could not speak Spanish on the picket line was a non-Latino Black worker who was leading the chant: “vendidos escuchan, estamos en la lucha.” This worker could not literally translate the phrase "vendidos, escuchan," but he understood the chant well-enough to know that it got the crowd going when he replaced "vendidos" with the name of the general manager or one of his scab co-workers. In that moment, he perhaps understood the language far deeper than someone who could translate a Spanish dictionary but would never use Spanish in their daily life, let alone a daily struggle.

This epitomizes the transcendent power of chants that results from the memeification of language, that someone can effectively communicate in a language that they do not “speak.”

For this reason protest chants are a powerful tool for building cross-cultural solidarity in this new age of labor activism. With the current wave of strikes across the United States intensifying across an ever growing number labor disputes, those in positions of power will attempt to use xenophobia and racism to divide the working class as they have so many times before.

But immigrant workers remain a growing force in the labor movement, and will not be pushed to the margins anymore. Spanish-language chants help pull these workers out of the margins by breaking down language barriers, and bringing us closer to an international solidarity not restrained by borders.

Taiyea is a Long Beach based composer, playwright, poet, field recordist, and performance artist. An “artist in anthropologist drag,” their research-based art practice involves extensive community dialogues which inform his use of music, sound, and language to explore issues of social justice.