· 12 min read

Lifers, Dayjobbers, and the Independently Wealthy: A Letter to a Former Student

Written by Max Alper

Last year, a private student of mine had gotten in touch with me via email at around 3 AM. I had known this student for years prior, as they were in one of the earliest college courses I ever taught when they were an undergraduate at CUNY. This student, now in their mid-twenties, had witnessed much of my growth as an educator, from a nervous graduate student lecturing a room of indifferent college students to Professor Shitlord Emeritus of the Internet.

I often take the feedback of students like these incredibly close to heart. I thrive on constructive criticism, and these students have seen the changes I’ve made to my lessons and teaching style based on their words and feedback over the years. So when I saw this person shoot me a DM at 3 AM the previous night, I was a bit concerned. No good DMs get sent at 3 AM, nothing good happens at 3 AM.

The student, who we will call Billy, starts off with the first sentence: “Hey Max, depression really sucks.” We’re getting right to it off the bat.

Billy tells me how much they’ve been struggling during the past few years, even before COVID, burning themselves out trying to make a living as a working musician in Brooklyn. It’s hard for anybody anywhere in the states to pay rent off their art. I can only imagine what it’s like to grow up an aspiring artist all the while watching your hometown turn into the hip stomping ground for wealthy transplants from the Midwest and other parts of the East Coast. If anyone should have a shot in the various New York music scenes first and foremost, it should be local kids like Billy.

So it breaks my heart when Billy tells me he feels like a failure in his own city. And because of the toll this has taken on his mental health, Billy says he’s giving up on music altogether and applying to trade school. I responded with a few thoughts for Billy, some of which I’ve expanded upon below, that I’d like to share with you all.

Dear Billy,

This breaks my heart on a few levels. For one thing, I’ve known you since you were a college student in my American Music History class getting your BA in Music. I thought I had done a decent enough job exposing the bullshit of the music industry to younger artists such as yourself, but one can only keep it so real in a college classroom without getting fired for telling their students that the game rigged.

What I wish I could have told you then is that every industry is saturated with nepotism and corruption, and oftentimes the arts are where these toxic qualities of the market get put on full display. We do not live in a meritocracy, hard work doesn’t automatically equal success when we are competing against those who have paid their way to the front of the line. But not to worry Billy, you have time to make your mark in your beautiful hometown of New York, let me tell you why.

Look at your favorite artists, alive or dead, the ones who you have always aspired to be as a professional. Chances are they have had one of three types of musical careers. Every professional musician I’ve met has fallen into one of these macro categories. I know it seems like an overgeneralization, but it continues to prove itself to be tried and true in my experience, so just hear me out.

The first of these three types of professional artists is the independently wealthy artist. I’m not saying look to the ones who flaunt it, you need to look for the ones with time. Often the most noticeable sign of merit on the surface level of a musician is their virtuosity behind their instrument. To shred is to impress, right? Yes, even I can admit that some good old-fashioned practice on a traditional instrument can indeed improve one's musical abilities tenfold. But this type of practice takes time, lots of time.

Who paid for all this time? How does someone outside of a conservatory program have the time to compose, record, and perform new original material every month, let alone to even practice their instrument an hour a day? The answer almost always comes down to the ability to not have to worry about paid work while pursuing your craft. As in, most likely, someone in your family pays your rent.

I’m not saying wealthy people can’t make incredible artists. Without Marcel Duchamp’s monthly allowance from his father throughout his adult life, we would never have Dada. Giacinto Scelsi was literally the heir and Duke of La Spezia castle estate. Something more contemporary? Grimes’ mother was a Crown Prosecutor, the Canadian equivalent of a District Attorney, in Vancouver. Frankie Cosmos’ dad is the guy from Wild Wild West, no, not Will Smith, the other guy. Julian Casablancas’ father ran New York’s top super modeling agency while young Julian hung out at the kid’s table with Ivanka Trump at Christmas time. The list goes on.

As talented and influential as these folks may be, it’s impossible not to link their artistic careers to the affluent lifestyles that supported them since birth. We can love their work while acknowledging that their upbringing most certainly is not the norm, nor is it something that your average aspiring artist can emulate in their practices. It’s like sprinting a hundred-meter dash while expecting to have the same shot of winning as the runner who is given a ninety-meter handicap. Time is money, and there will always be people out there who have more time than you to pursue their passions. So, fuck ‘em dude, you work with the time you have, it’s not a race.

The second general category of musical career is that of the lifer, or one who has dedicated their life to the struggle of making a living solely as an independent working musician, for better or worse. There’s never a better time to be about that life than when you’re young. You’ll never know it ain’t for you unless you try, and you got the energy for it in your early twenties. Being about that life includes, but is not limited to, tour nomadism, working seven days a week across multiple musical projects that both gig and record, and relying solely on the income generated from said touring and bands. This usually means not making much money, especially in the COVID and post-COVID world. Not to say you can’t make decent money off Bandcamp sales when you have the right amount of presence on the internet, but the effect of the pandemic has without a doubt been crippling to working musicians. As smaller venues closed across the country, private equity moved in.

In our contemporary hellscape that is the recording industry, gigs and direct in-person sales of merchandise are essential. For all the good that the monthly Bandcamp Friday series has done both during and after the pandemic, which included waiving all sales fees for artists to yield 100% revenue on the first Friday of every month, mass adoption of streaming platforms as the main means of record distribution has all but cemented the death of recorded music on its own as an asset of monetary value.

Not to say lifers playing the game by industry standards had it good before streaming, artists have been getting fucked over on royalties and rights to their masters since the phonograph. What makes our contemporary record industry different is that it has merged with platform capitalism at its highest level of infrastructure. One simply cannot survive off streaming alone without a means of getting playlisted by the platform algorithm, which often incentivizes those that can afford to game the system to do so. Streamfarming, algo-boosting, and paid bots have become quite profitable industries if you know where to look. If companies like Spotify can't make a profit and are propped up by shareholders, how should you be expected to earn a living using their platforms unless you find a way to game the system? Do you have 20 smartphones lying around, per chance?

For an artist, choosing to not engage in self-promotion via streaming or social media platforms is in and of itself an act of protest. To knowingly cut oneself off from an algorithmically boosted audience makes it that much harder for an artist to get heads out to shows to pay full price at the door and buy merch directly after the concert. Hell, even I am married to the platform as an independent music teacher at this point. Instagram can get heads through the door, unfortunate as it may be, it may be the reason why you’re reading this letter at all.

With the way the cookie crumbles, Spotify and other streaming platforms can that much more likely get you a Bandcamp sale from someone who discovered you while scrolling the algorithm. To live that life as an online musician means to constantly release work across all platforms, to take advantage of every Bandcamp Friday. Any potential means of monetization is worthwhile, hustle equals survival. It's the sigma grindset on a quest for minimum wage.

The founder of Spotify, Daniel Ek, tells us that artists need to make more work if they want to benefit from the new systems in place. Nothing has changed for lifers. Hustle hard, no sleep. Believe me, just because I am acknowledging the sad truth doesn’t mean I don’t want to burn it all to the ground in a blaze of glory. Or at the very least demand a Spotify healthcare plan for any and all artists on the platform in a country that otherwise won’t provide it for them. A boy can dream. I digress.

It’s because of this harsh reality that romanticizing the lifer lifestyle in 21st century Brooklyn, or any other major American city, as anything other than the struggle it is can be incredibly dangerous. Millennials and Zoomers have been sold the lie that the big cities remain a bastion for cutting edge arts and culture, let alone that they are even livable for working artists. What year do they expect us to believe it is? The New York Times loves to gloat about the local renaissance happening in Bushwick in the Arts Section while covering a tech CEO who recently bought a brownstone in Bed-Stuy for a cool five million in the Real Estate section.

No-wave New York and its grandchildren are all but dead when rent costs as much as it does. The Lower East Side is a weekend playground for New Jersey’s most drunk. People who live in a closet in the shadow of a Chinatown fish market on one side and the Manhattan Bridge on the other pay upwards of $3000 monthly for the privilege to do so. The ground level of McKibben Lofts is now home to yoga studios and organic markets. The live/work loft space of the solitary working artist in the 2010s is nothing more than a leftover set on a soundstage for HBO’s Girls, unless you’re looking for nine roommates.

The Lifer game is an uphill battle in the big cities, where nightlife can be both the main source of income for many, while also being the major contributing factor to the rising costs of living. It’s for this reason that I assume that some of the most successful lifers I’ve encountered have made the bulk of their careers outside of the big cities. Those that have sought a smaller, tight-knit community over a larger scene, a sort of preferred intimacy over a massive reach, are bound to find it wherever they end up. The lifer game is a social one first and foremost. It’s one of survival, but also one that requires a greater community to prosper. So as long as we put ourselves out there as a resource and provide a means of putting each other on bills and a place to crash whenever a head rolls into town, DIY will never die, struggle it may be.

The third and final general category of musical career I’ve encountered, and the one I’ve found myself in for some time now, is that of the Dayjobber. It’s the category you seem to find yourself falling into, Billy; a line of work you claim makes you a failure as an artist by choosing to enter. I wish I could strangle you through the computer screen, Billy, lovingly, of course, to snap you out of the toxic mindset you’ve found yourself in. Okay, no strangling, how about a very stern bearhug?

Not only are you not a failure for coming to terms with the fact that you’d prefer the peace of mind and mental health benefits that financial stability outside the arts can provide, but you’re also that much more of a professional artist as a result of this acknowledgment. A day job not only pays the bills, but also provides a necessary break for your ears and brain. You know your work requires sustenance, time and money doesn’t grow on trees, so you seek to build a cushion to support your artistic practices. It doesn’t matter if you’re not practicing every day or gigging every weekend. You make it work on your terms, at your own pace. It’s more than what most do in their adult age. At least you're fucking doing it.

I’m telling you this as a guy who has never paid his bills off gigs and record sales alone. I make fucking noise music and walls of ambient textures, dude, I don’t expect to receive a big advance from Atlantic or Sony to crank out my algorithmically generated pulsating meter nowness anytime soon. I came to terms early in my musical career with the fact that I needed to find a trade if I wanted to pay my bills and continue to pursue my art. The key is finding something you’re actually good at.

When I was in college, I spent my weekends working as a direct support professional for various schools and learning centers for kids in New York with special needs. The plan at the time was to just get into special education at the vocational level out of college. The work was gratifying and steady on its own and I was a decent teacher, a music-related profession wasn’t even in the cards at the time. It was only through years of working as a DSP that I eventually started to plan out syllabi that combined both K-12 education and music technology.

This ultimately pushed me to go to graduate school for an MFA in Sonic Arts and Electronic Music. Hey, Billy, this was when we first met! I was only a humble, broke, and eager graduate student working as an adjunct music instructor and studio assistant when you enrolled in my Music in Global America class. I didn’t re-enter the academy simply to better myself as an artist, I did so to expand my abilities to teach, talk, and write about music technology. Words, education, and technology are my trade, it just so happens that it now relates to the words, education, and technology of music on a full-time schedule.

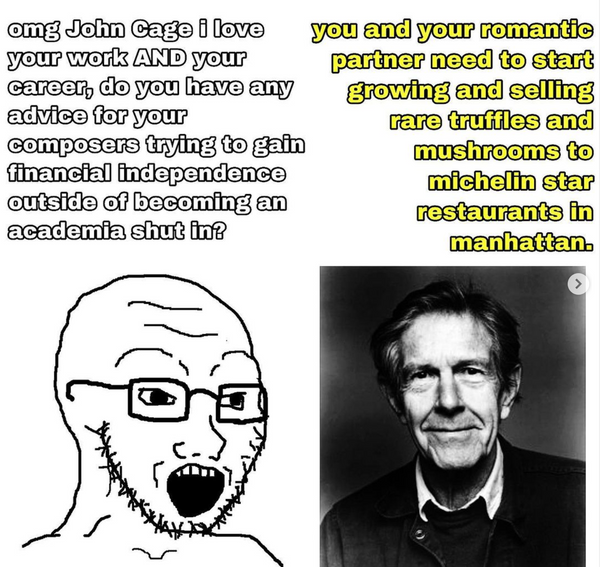

And I am by no means alone in my pursuits to pay my bills outside of gigs and record sales. Philip Glass, boring as I may find him, is a hero of mine in this regard. He has gone on record to say “I expected to have a day job for the rest of my life”, having worked alongside fellow minimalist Steve Reich and sculptor Richard Serra as a moving company in the 1960s, as well as a cab driver up to (and during) the premiere of Einstein on the Beach in 1976. John Cage never stopped foraging for rare mushrooms and truffles - what was once his primary skill for sustenance during the Great Depression had transformed into his main source of income well into the peak of his career as a composer and public intellectual. Michelin Star restaurants in Manhattan paid top dollar for Cage’s occasional fungal findings upstate, enough to make sure he could spend the majority of his time composing and writing, sometimes with and or about mushrooms themselves. Charles Ives never stopped selling life insurance. Fenriz, of Norwegian Black Metal pioneers Darkthrone, never stopped being a postman and a union member. The list goes on.

You’re not a failure by being a dayjobber, Billy, you’re an artist, just like the rest of us. So what if you aren’t some rich kid from the Upper East Side who had the privilege of being stuck in a practice room since Kindergarten? Sure that kid can shred, but do you really want to be that person? You’re playing shows, making records, and selling merch online, all without daddy’s money to hold you down. You’re making it happen without the head start that Richy Rich got the second he was born. Be proud of that! Knowing that the game is rigged is liberating! Just because the music industry lacks meritocracy doesn’t mean you can’t blow these assholes out of the water through your craft. Your experiences outside their bubble will only foster more creativity as a result.

So what if it takes a bit longer because you can only dedicate an occasional evening or weekend to work on your new record? So long as you dedicate yourself to that time, as little as it may be, so long as you allow the public to hear what you’ve been up to, whenever or wherever that may be, Billy, then you’ll never be a failure. You’re still alive, aren’t you? Then you can make the time, but no rush.

Your former professor,

Max

Max Alper aka La Meme Young is a composer, educator, writer, and cultural worker. He is the cofounder of Klang Magazine and performs music under the moniker Peretsky.