· 12 min read

On Mentorship, Labor, & Scene Politics

Written by Max Alper

I’d like to tell you a story about how I came to understand the labor dynamics of the New York experimental scene in the early 2010s, and how hungry young artists are often the easiest to exploit for their labor within creative industries at large. For the sake of civility, certain names, venues, and band names will be withheld and given pseudonyms in quotations. While much of these stories are specific to the five boroughs, my hope is for all aspiring young artists to be able to use this as a reference point when seeking mentorship and approaching their own self-worth.

As young people, we’re told we need to cut our teeth in our creative field through whatever opportunities arise. It’s expected for you, the young artist, to have to eat shit and smile. This could be through an unpaid internship, an entry-level position, or maybe, an artist you admire decides to take you under their wing as their mentee. You get them coffee, organize their desktop, and maybe, you’ll get to see how the sausage is made if you play your cards right. With so many fish in this massive sea, the fact that we’re given a shot at all is something we’ve been told to be grateful for. There’s a whole crowd of people that would kill to be able to work at this venue or with this artist, etc.

This is how I was taught to make connections in the NYC experimental music scene. But more importantly, I was taught this by people who knew all too well that they could take advantage of my clear eagerness to insert myself into something I had only watched from the internet for years prior. Many of the people who opened the door for me did so under false pretenses, and by the time I figured it out, it became that much harder to step away. If I knew in 2012 what I now know more than a decade later, I could have avoided a whole lot of stress, gaslighting, and emotional abuse at the hands of a select few tastemakers in New York nightlife.

I moved to New York in 2009 to attend Purchase College in Westchester County, later dropping out, and transferring to Brooklyn College. Moving into New York City proper in May 2011, I used my semester gap period to hang and gig with as many musicians as I could meet. During this time, I came to realize just how accessible and down-to-earth many of my idols were in the Big Apple. After finishing a dog walking shift in the Lower East Side in 2011, I would often pop by the brick and mortar Hospital Productions record shop, owned and operated by Dominick Fernow of Prurient, Vatican Shadow, and Rainforest Spiritual Enslavement fame. It astonished me how easy it was to just pick the brain of someone whose work I had admired since I was 15. Despite having just released a pivotal record of his own, “Bermuda Drain”, and the need to answer his phone every other minute for an interview with the press, when Dominick was around he was really around.

I didn’t need to strike up a conversation. Like any proper record salesman, he got all in my business:

“What are you into?”

“I dunno, I like noise and free improvisation, *notices NSBM vinyl*, not much into this type of Black Metal though.”

“You should get ‘C-Section’, a recent collab record from Evan Parker and John Wiese, some pretty heavy improv here.”

“Okay, I will, thanks Dominick Fernow of Prurient.”

“Do you play noise and free improvisation?”

“Yes, I only recently moved to the city and would love to play some shows with whoever would want to.”

“I don’t want to, but you should talk to ‘Bobby Baby’, he recently moved to the city too, do you know him?”

“I know of him, I love his music, what’s his cell?”

“I’m not giving you his phone number, just add him on Facebook.”

“Okay I will do that, thank you Dominick Fernow of Prurient.”

I’m paraphrasing here obviously, but that’s basically how it went down the first and only time I really chatted with Dominick for more than a minute. But I took his advice. I reached out to Bobby Baby and we played a show I organized in a storage space turned art gallery in Bushwick. I made some new friends - it was great. And it was through Bobby that another gig arose, one that would end up being a pivotal moment in my musical career. Bobby was booked to play a set for his friend’s — let’s call him “Joe Janky” — ongoing Monday night series at “PoopScoop” in Williamsburg, a pivotal venue that I managed to catch the very end of before it got priced out of its primetime location. Bobby knew he wasn’t going to be able to make Joe’s booking that night, so he asked if I wanted to fill his slot.

I was kvelling, to say the least. Not only was this a prestigious venue that I had only visited as an audience member, but Joe Janky was the founder of one of my favorite bands as well: “the Booboo Doodoos”. I knew I had to give this gig my all and set myself apart if I wanted to get the attention of this scene vet. I decided to do a collaboration set with my roommate at the time, a choreographer and improvisational dancer named Claire. I chanted Jewish liturgy-inspired vocal incantations through a glacial wall of delay, reverb, and loop processors as Claire squirmed, stretched, and contorted in an equally slow fashion. (In hindsight, I wish I had recorded a video of the set that night. It’s one of my strongest improvisational performances to my memory and Claire and I really bonded during these performances.)

But we weren’t alone in feeling gassed up after our thirty minutes were up. The loudest applause came from Joe Janky himself, and I was absolutely flattered.

*Is shitfaced* “Y’all absolutely killed it!”

“Wow thanks so much, Joe, I really appreciate you letting us play tonight on your bill, I’ve been such a huge fan since high school!”

*Wasn’t listening* “Do you want to play in my improv ensemble at the “Bing Bong” next month?”

Holy shit, this was major. Here was Joe Janky himself, blitzed out of his mind, hanging on my shoulder, telling me he fucks with my shit and he wants me in his birthday noise band at the fucking Bing Bong? Obviously, I said yes — what idiot would turn this down in their early 20’s? The show at Bing Bong was nice. Joe, myself, and five other veteran musicians, including Bobby Baby, played in free improvisational round-robin-style to a sold-out room.

The original Bing Bong was in a tiny little storefront on an East Village corner, and it could hold maybe fifty people at legal capacity, but managed to charge a relatively high number at the door. This was a place for real heads to support their favorite experimentalists up close and personal. And yet despite the full house, I didn’t get paid shit that night, but I was too stoked to care to check in with Joe at the end of the night regarding door money. I figured this was definitely me being put on to some heavy hitters who were my superiors in the scene, so it didn’t matter if I got a cut. “This could lead to even sicker opportunities down the line.”

Let’s put a pin in that, shall we?

The following week, I emailed Joe to thank him for the opportunity and to ask him for his professional advice. Here was a guy who seemed to have his shit together — he was touring constantly, putting on awesome shows throughout the city, releasing vinyl for both his band and his solo project, all the while still holding down a day job as a music educator in the non-profit sector. I told him how I aspired to get to his level someday, but being in my early twenties and still fresh to the city, I had the self-awareness to know I couldn’t do it alone. I sought mentorship, and Joe had a way about him that just got you excited about whatever was on his mind. So when he said we should start hanging at his crib every week so I can assist him with projects and work with some of his heaviest collaborators, it was a dream come true.

There were red flags right off the bat that I wish I had the foresight to see at the age of 21. The first time I met Joe for one of our weekly sessions, he spent an hour telling me how I actually had it all wrong, how he and I were in fact “equals”, and that my work as an artist was just as valid and forward-thinking as his. We listened to some of my recent tracks, he seemed to show a real interest in listening to what I was up to sonically. Needless to say, Joe had me stoked and feeling special, and he knew it.

He said he was never really super comfortable with DAWs and computer music, and in fact, he could use my expertise on some upcoming projects on his to-do list. He had just been signed to a pretty big label, as far as experimental indie imprints in New York go, and he was tasked with making a mixtape of original performances and remixes of other artists on the label to be released through their official channels. There was also a remix project for an EP release that needed to be at least 7 minutes. Two projects, two collaborators in the home studio. Seemed simple enough.

What I didn’t know was that I would be doing 90% of the work and taking 0% of the credit. I pieced together the original stems, recorded and mixed the new materials, and mastered everything to the best of my abilities. Meanwhile, Joe hovered over me while on the phone talking to the press about said projects, or sat at the other side of the table with headphones on answering emails. When the projects were done and published by the label, I asked if there was going to be any pay involved as he had mentioned he was already getting a decent amount of presales on his new solo record. It was then and there I saw the darker side of Joe for the first time, one that would remain hovering over our relationship for the next three years:

“Why would you even bring that up? You realize how much you’re embarrassing yourself right now, right?”

“I don’t follow.”

“You told me you were down to help, you never said anything about a monetary exchange for the projects we work on together. Do you realize how many folks I know who’d just be down? I’m helping you here.”

This was standard manipulation and emotional abuse in the workplace right here, but how the hell would I have known that at that age? The dark vibe continued, but I stuck around even as more red flags popped up. Joe had introduced me to so many genuinely amazing artists, and he had even gotten me a job doing sound at a new music venue he was helping manage. I was helping with his weekly concert series in Williamsburg, the same one I had originally met Joe at earlier that year. And by “helping” I mean I was running them on my own for drink tickets on Monday nights while Joe had dinner at home with his family. Each month there would be a different co-curator organizing the bills, and each month they’d come find me afterward and ask me when they’d be getting paid for their month of curatorial labor.

“I’m sorry, I really don’t know, you have to ask Joe” was all I could say.

And each month I’d hear something from Joe along the lines of “Yeah, it didn’t really work out with that curator” after I’d stop seeing them at the weekly shows.

Little did I know, Joe Janky was a bit of a legend when it came to just how many bridges he had burned in the scene. That only became apparent to me after he became co-owner of an L-train experimental music venue that teetered on the fence between an illegal rave basement and a legal avant-garde bar. Joe’s business partner, who we’ll call “Donny Don”, was quite the staple in the Brooklyn DIY circles, as he was the guy who got the liquor licenses and the cheap warehouse leases. It seemed to me that the main reason that Donny had so much clout was his relationships within the real estate industry, which, as it turns out, is the nightlife industry.

A venue pops up in a gentrifying neighborhood, new young transplants in college come out to a show in said neighborhood, and now a familiarity with the area is born and these young folks are that much more likely to want to rent an apartment in the area. More venues, coffeeshops, and yoga studios start to pop-up as the rent gradually increases. Artists move into new neighborhoods at a time when they’re cheap and inevitably cannibalize themselves and those that have lived there for generations out as they’re replaced by finance bros and closeted republicans with Masters degrees and podcasts. It’s a tale as old as time in a city that cares more about growth in property value than the livelihoods of its most vulnerable residents.

“Say what you want about him, but Donny just makes it happen for the scene” is what Joe would say whenever anyone would question Donny’s almost cult-like status as a New York nightlife tastemaker. In 2012, you couldn’t argue with somebody who could get your rave a temporary lease off an L-train stop you’ve never heard of.

This new venue they opened together, which I’ll call “Rango Bango”, was run by a constantly rotating staff of hungry young people, myself included, eager to envelop themselves in all things DIY and experimental music. This, of course, meant we were all paid shit, but what Donny and Joe would tell us during staff meetings was that we were cultivating a true community with the work we were doing. Then, they would go off to drunkenly pose for a Pitchfork photoshoot in the basement while the rest of us mopped up and counted the cash.

On top of the work I was doing running sound for the venue until the wee hours, I was now also helping Joe with his teaching work. While I do have Joe Janky to thank for encouraging me to take the path of experimental music pedagogy, which I still walk to the day, this encouragement would also lead to our final falling out.

Joe sparked a fire in me to take music education seriously. I started applying to new jobs in the non-profit sector and within the NYC Department of Education. I knew in the long run that I didn’t want to live the lifestyle of an experimental music venue sound engineer. I enjoyed waking up a reasonable hour and getting paid a reasonable stipend for my labor, after all. But the more ambition I showed in my pursuit of a higher position, the more pushback I received from Joe:

“You need to chill with the off-hours work you’re doing, most people usually plateau in their careers in order to succeed later on. I need your help here.”

What the fuck was this guy talking about…a fucking plateau in my career? Here I am, 24 years old and fresh out of college at this point, being told by my 40-year-old mentor to slow down in my ambitions so I can help him with his? Bullshit. By this point, I had met enough of Joe’s former colleagues to understand what his manipulative tactics looked like. This dude was fucking manically stoked on whatever you were doing one second, and then laying into you for not doing enough for him and his projects the next:

“In a real professional relationship there’s a two-way street, I’ve helped you out so much, introduced you to so many heads. You need to be able to help me now.”

What does working ten-hour shifts until 4 a.m. for sixty dollars total while you and your business partner get drunkenly interviewed in the beer garden by the Times look like? Is that not helping? I had to get out of this workplace. Everyone I started with at Rango Bango had quit months ago, why the fuck was I still here?

I jumped ship in the spring of 2016, four years after my working relationship with Joe Janky began. Shortly after I quit, Joe and Donny had a falling out, ultimately leading to Joe himself quitting in pursuits of greener pastures. Donny would later tell me that Joe was insufferably “all about his check” while delegating his responsibilities to everyone around him, including his business partner. I’m not saying I sympathize with Donny and his frustrations with Joe, as he was certainly his own breed of a shitty boss, but at least Donny didn’t make you feel like a million bucks before crushing your soul as Joe Janky would. It never really felt like Donny was my friend and I actually appreciated that from him.

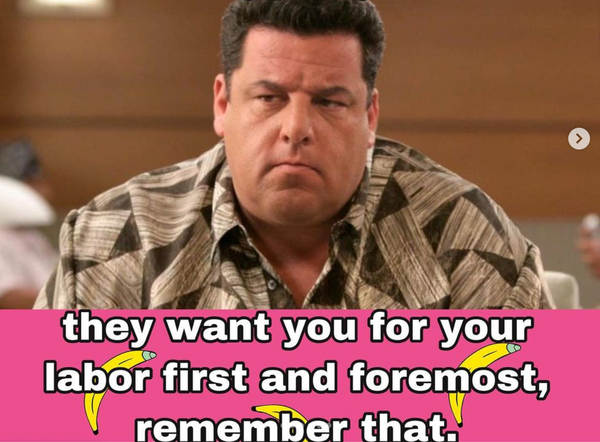

Seven or so years later, long gone from my early days of Brooklyn DIY, I now know my story was not unique in the slightest, nor was it specific even to the music or nightlife industries as a whole. Everyone seeks opportunity in their field, and there are always mentors, managers, and people with power —all willing to take advantage of that to increase and raise their own bottom line. Capitalism requires hovering “opportunity” over those most desperate, like a hot dog on a stick attached to a dog’s collar, all to maximize yield from their labor at the lowest levels of compensation.

You’re not a “collaborator”, you’re not their “equal”, and if someone trying to put you on an opportunity to get free work out of you tells you this, they’re lying. The potential opportunities promised in your field should never outweigh your well-being and dignity here and now, regardless of your age or entry level. A mentor that preaches collaboration while seeking to leverage your creativity for their personal projects is not a mentor at all, but rather your standard wage abuser.

“Do you know how many folks would kill for this position at your age?”

“Do you know how many guitarists would kill to play in my band?”

“Do you know how many bartenders would kill to work at this club?”

“Do you know how many econ majors would kill for this hedge fund internship?”

If a person you admire in your professional field hits you with this, wherever you are, run. Just my advice.

Max Alper aka @la_meme_young is a composer, educator, and writer, and is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Klang Magazine.