· 9 min read

The Klang Magazine Handy Dandy One Stop Listening Manual

Written by Jay Afrisando

“Listening” is perhaps the weirdest term in sound and arts practices.

- “Listening” is like Forrest Gump—it’s everywhere. We know it’s essential... but do we actually? People assume they know how to do it intuitively. It seems trivial and given.

- Music education offers listening classes less than of history, composition, theories, or even solfeggio. Some possibilities: it’s less attractive, it’s taught in a way to support a particular agenda (like a certain group’s musical hegemony), or it’s already integrated with other courses so it’s irrelevant to discuss in depth on its own.

- Many problems seem to emerge from our ignorance or abuse of listening: noise pollution, dependency towards passive internet algorithms, superiority over other (non)living beings, and so on.

- Open your search engine and type “art of listening” or “how to listen.” The entries you’ll get are mostly about honing human communication skills in the workplace. Frowning face.

Here’s the thing: Listening is the first gate to making sense of the world, from ordinary, everyday activities to specific tasks in the field. Moreover, our making sense of the world affects what we decide and do for individuals and communities, from assessing preferences to making governmental policies.

Many resources about listening tend to either focus on specific scopes or are geared toward human communication skills. On the other hand, finding a comprehensive listening resource containing various perspectives in plain words is perplexing.

We’ve taken listening for granted. Admit it.

So, I wrote this one-stop resource on listening for Klang Magazine. Of course it can’t cover everything. But hopefully it’s comprehensive enough to help us learn, relearn, and unlearn our ways of listening and be better and more ethical listeners.

This guide draws from various topics, including sound studies, composition, psychology, and aural diversity. It’s also based on my 13 years of experience practicing and learning from diverse mentors and fellows. To me, writing this guide felt like practicing listening from the very beginning.

Whether you’re a musician, a field recordist, an art curator, a writer, a patron, a gardener, a cook, a scientist, a politician, a high school student, or a stay-at-home mom/dad, this Listening 101 is for you. Smiling face.

[…]

Things to note:

- There is no one-size-fits-all way of listening.

- Listening is like a muscle—training is paramount. Don't overwork yourself or you'll burn out.

- All the aspects below intertwine with each other.

- We should continuously evaluate our ways of listening.

The WHO

First and foremost: Who is listening? A human? An animal? A machine? All of them listen differently.

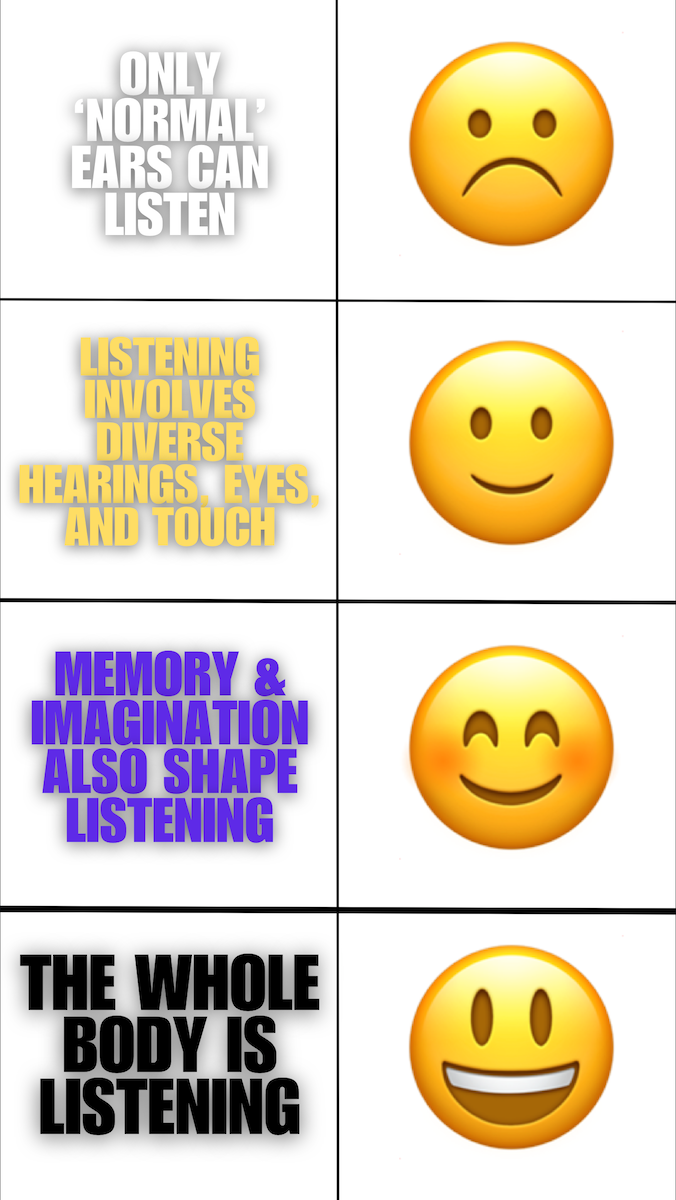

Humans alone have diverse listening experiences physiologically. d/Deaf people, cochlear implanted and hearing aids listeners, persons with hyperacusis or presbycusis, people having Ménière’s disease, autistic persons, those experiencing Noise-Induced Hearing Loss due to exposure to loud sound, blind and low-vision people, DeafBlind listeners, and many more all have varying exposures to listening.

No one has the same body anatomy, so no one listens in the same way. Unfortunately, the world is created to favor ‘normal’ and idealized hearing. Some examples are auraltypical problems in sound arts practices, sound studies’ inclination toward a nondisabled hearing subject, the ideas that music is only about sound and d/Deaf people don’t have a position in music discourses, and many more.

This doesn’t get into a broader discussion. We should change that.

The idea of listening through less-than-"perfect" ears might be alien to the hearing world but not to aurally diverse people. When we’re signing, we’re listening to a din of language in our head. Even without cochlear hearing, sound inhabits our world. Quite frankly, our body’s sense of touch is essentially a hearing apparatus. Listening with tinnitus tells us the concepts of sound and silence are biological and political. And through aurally diverse listeners, we know that the soundscape is never singular. These are just a few examples.

Aural diversity should be the ground of whatever we conceptualize, sound- and listening-wise. That includes not only music but also arts in general, design, architecture, psychology, audio engineering, and philosophy, to name a few.

The HOW

Use what we have to listen. Ears, eyes, skin on fingers and feet, chest cavities—our whole body is a collection of listening devices. Some of us listen through residual cochlear hearing, hypersensitive hearing, eyes, hands, or combinations.

The brain also plays an essential part in listening. It’s through imagination that our understanding of sound always involves physical action, making our sonic experience multimodal. Visual, motor, and tactile skills, which shape sound-generating images, may evoke sound images and vice versa.

We experience the twofold of hearing-listening that goes hand in hand. Human external listening devices HEAR in the same way that different microphones and transducers capture stimuli. The brain LISTENS to the encoded signals, like a Central Processing Unit. The brain is always busy decoding incoming signals (from ears, eyes, and body) and processing rich inner aural experiences.

Through aural diversity, we also know how critical empathetical listening is. Listening through other humans—nonhumans, too—will develop our sense of position. Each of us listens differently, so listening through others will allow us to shape a more holistic idea of what sound is.

Besides, what mediates our listening affects how we listen. Headphones, loudspeakers, hearing aids, cochlear implants, different audio/video players, audio file qualities, and various solid matters bring us various listening experiences.

Another “how” is to vary our listening methods: skimmed, slow, repeated, and zoomed-in listening. This especially relates to the next part:

The WHAT

We’re accustomed to pinpointing what we hear with the generating source. We notice what we hear may be a car. A cat. A train. A scream. But listening to its structure, especially observing the sensation beyond associating the stimulus with the source, is something we’re unskilled in.

Like, what does your car sound to you: edgy-crumbly, distorted-metallic, painful? What does your typical morning sound to you: crammed, piercing-bright, spacious? Next, observe their relationships with the surrounding environment. Notice the rhythm of all the party involved relative to seconds, minutes, days, and years. When do sparrows nearby your apartment start making calls? Are the calls sparse, intermittent, imperceptible? How are they living with other birds and humans? What does the whole sounds of the birds, the humans, the machinery, the wind, and the sunlight sound to you? Etc.

Focusing on the quality of the stimuli and training ourselves to describe them is rewarding and shows to what extent we really understand what we listen to.

It also applies to other sensory activities, like seeing, feeling, and tasting. You’ll be surprised: Focusing on the stimuli’ characteristics will teach you to respect the generating source, be it sound, visual, vibration, or flavor. This activity will also enhance each sensing apparatus we’re training at.

‘Normal’ hearies should learn from autistic listeners, who were reported to have enjoyed detailed listening, soundscape decomposition, and zoomed-in listening. Listening through skimming, slowness, repetition, and "zooming in" helps us navigate what we are perceiving. Repeated and prolonged listening especially allows us to get the fuller shape of what we’re listening to.

But be careful of what we’re listening to repeatedly, even when our attention is paid elsewhere. We tend to like it after mere exposure, and the mainstream industry knows this too well.

Besides listening to what we can hear, let’s pay attention to what we’re not hearing. What does it mean to listen to a ‘modernized’ neighborhood in your area, to music processed through AI-powered plugins, to a playlist generated by your favorite streaming platform’s algorithm, to endangered species outside their natural habitats, or through a stethoscope inaccessible to hard-of-hearing medics?

Here, we listen to what has/had formed the stimuli we’re perceiving. It may mean paying attention to gentrification, late capitalism, colonialism, or ableism—or our ancestor’s compassion, Indigenous ways of living, or individual and communal efforts—among others. We should make a habit of listening to “the listened”’s historicity as sound is always tied to culture, history, and memory.

Additionally, we should listen to anything beyond our favorites. Listening to what we like is easy. Listening to what we dislike? Now we’re talking. I’ll explain this more in “The WHY” part.

The WHERE

Space matters.

An echoed big hall, a dry bedroom, a prairie, and a crowded downtown will give us distinct listening experiences. A pack of people will absorb acoustical reflection; solid walls will echo-cho-cho-cho the sound. Air, water, and solid objects as propagating media also affect our aural perception in terms of shape and timing.

This isn’t just about acoustics. It’s more about soundscape, both the physical environment and perception of that environment. Soundscape brings a sense of culture—to some extent, its social circumstances may dictate who gets to hear what. It’s bizarre, but we don’t realize it often—except recently when LA and a 7-Eleven owner blasted Western classical music to keep homeless people away.

Space can also determines whether an environment one’s occupying is supportive or damaging, as in hospitals, restaurants, and schools.

Paying attention to sounds and visuals individually helps us assess our listening. I once audio-recorded crowds in Times Square. I listened to the audio individually. I was surprised by how the visuals are far noisier than the sounds—the visuals colored my aural perception.

Listening to the space means paying attention to the noise we’re contributing to society, including spaces we build where the sound is occupying. This is why acoustics and inclusive design for people with diverse hearings are vital. Interestingly, this is how sign language excels—not only it allows Deaf people to communicate in an acoustically noisy space, but also beautifully puts human noise in shared, private spaces in the mind.

The WHEN

It’s pretty straightforward: Listening when energized and tired gives different aural perceptions. So, it’s always a good practice to rest when we start to perceive everything muddy after prolonged listening, especially in an acoustically/radiantly intense environment.

Different times of the day also affect our listening. The acoustical energy travels faster yet shorter during the day and slower yet farther during the night because of how molecules gather and layer. So, the next time you make sound at midnight—like blasting your favorite playlist or blaring your vehicle engine—think twice, at least for your neighbors' sake.

The WHY

We may have thousands of reasons why we’re listening. But we haven’t emphasized enough why we’re listening, especially learning the damage we’ve done because of how we listen, which can sometimes be hostile and discriminatory.

Here, I want to emphasize two reasons.

First, we listen to appreciate.

Often, a war of preferences happens simply because we argue our favorites are the best. Mocking each other’s preference won’t benefit us or the audiences spectating our irrelevant debate. We don’t give meaningful values to what we’re listening to, so we don’t provide those values to other listeners. More harm than good, yeah?

How do we avoid this? Listening to the stimuli’s characteristics and what we’re not hearing will help us train to temporarily set aside our taste and unpack what we can value about things we dislike.

An example. More than two decades ago, I loathed Indonesian dangdut music just because other people I knew hated it too. How snobby I was. But then, a decade later, I tried to listen to it carefully. At first, I immersed myself in a playlist. Next, I observed the sonic-visual characteristics of the music. Then, I read some stories and the artists’ profiles. Finally, after a few months of listening, I realized dangdut has rich aesthetics and history.

Although I eventually started to like it, the goal of listening beyond my preference is to learn the characteristics and comprehend what I wasn’t hearing in my listening. It’s okay if you keep disliking something after slow, prolonged listening. It’s just not for you, but you get meaningful takeaways.

Once you value things, you’ll bridge a meaningful conversation and respect anything you listen to. You may also get benefits from learning outside your preference. It also applies to seeing, feeling, and tasting. So, while you listen for appreciating, try to do the same with tasting, seeing, and feeling.

Second, we listen to witness.

Listening is basically a form of field recording. When we’re listening, we’re recording. We’re witnessing. We are taking notes. We’re there, never invisible.

But we bring cultures, histories, and memories with us with each listen. They make us partial and biased, just like the technology that’s never objective and the field that’s never impartial. Everything we listen to is tinted. We process and embody the field we’re listening to become our knowledge. Then, we share this knowledge with other witnesses.

Knowing that we’re witnesses, it’s a reminder that other people and entities—birds, squirrels, cats, etc.—are also witnesses. They listen and record what we’re doing. Nonliving entities, like technological tools and materials, are witnesses, too—they bake evidence of humans’ doings. Some sound studies scholars prefer “listening with”—instead of “listening to” as it makes “the listened” a partner instead of an inanimate object.

What can we learn from this? We have shared responsibilities of always being aware of what we’re listening to, which was and has never been neutral.

“Listening to witness” sums up what we should do as a listener:

- Always be mindful of what we’re listening to.

- Be careful of what we’re perceiving.

- Be sensible about what we’re constructing.

- Be conscious of how we listen.

Everytime, everywhere.

Even if we listen for leisure, we should always be proactive in knowing how different people perceive different soundscapes, how and where such sounds came from, and how such an environment was structured that allows our listening.

Jay Afrisando is an Indonesian award-winning multimedia artist, composer, researcher, and educator working on aural diversity, acoustic ecology, and cultural identity through multisensory and antidisciplinary practices.